While ALEC has had success for many years pursuing its agenda, it is not without vulnerabilities. Advocates, activists, and movements seeking to push back against its corporate-first, racist agenda can take meaningful action to resist ALEC’s influence over law and policy-making and reclaim the people’s right to self-determination.

This section is designed to facilitate generative strategizing for advocates. Specifically, in the spirit of cross-movement solidarity, this section will draw on past successes by progressive grassroots movements for social justice across issue areas – often but not always battling ALEC-sponsored legislation – to suggest a way forward to reclaim our law and policy-making spaces from corporate control.

Political Advocacy Opportunities

With an increased presence of progressive politicians in federal and state legislatures, there are a growing number of opportunities to take on corporate control of legislative decision-making through political advocacy.

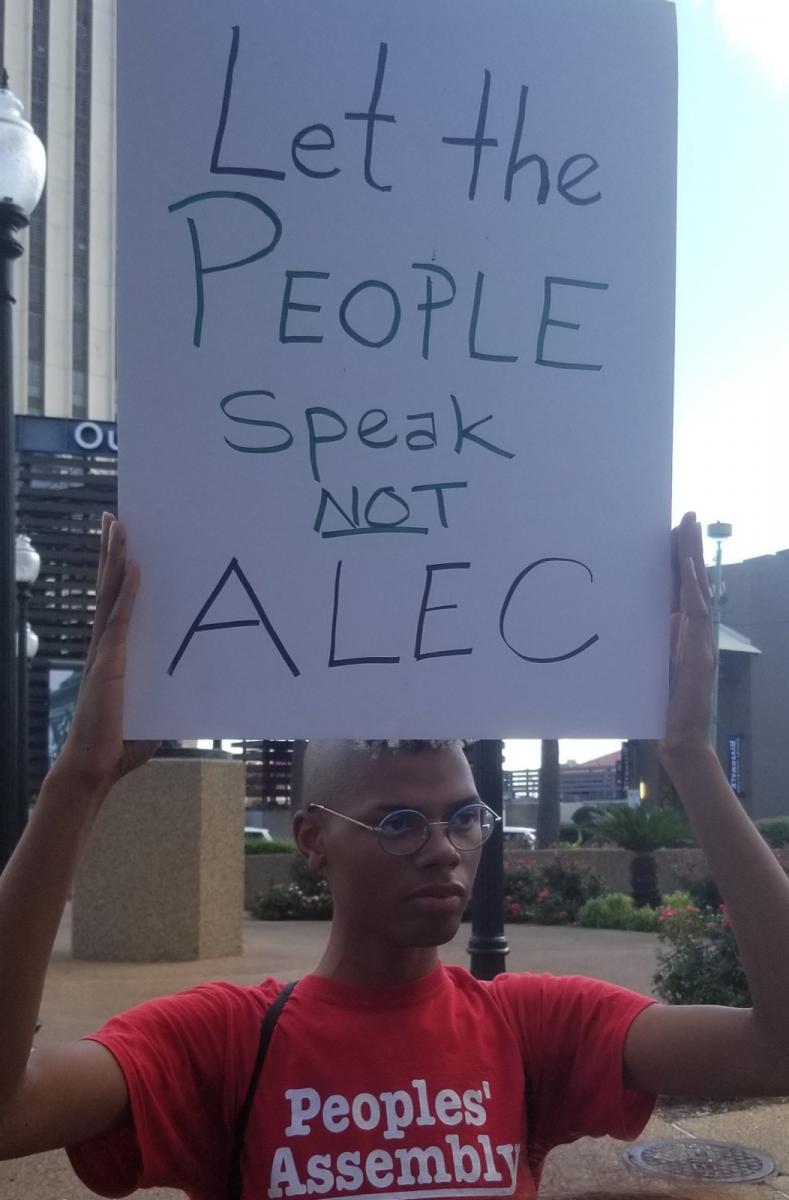

Calling on Elected Officials and Corporations to Cut Ties with ALEC

As demonstrated by the group Stand Up to ALEC,[197] a viable advocacy approach is to make sure state lawmakers know that their constituents do not want them associating with ALEC. Key times to mobilize constituents to register their concerns about ALEC with their representatives are during political primaries, in the lead-up to state elections, and in the recess period before state legislatures convene.

[197] Stand Up to ALEC, “Stop the Swamp,” https://standuptoalec.org/stoptheswamp/.

Although it is not always easy to know whether an elected state lawmaker is a member of ALEC (as explained above, ALEC does not identify its members are unless they are part of an ALEC Task Force), groups like Stand Up to ALEC,[198] the Center for Media and Democracy,[199] and Documented[200] have all compiled information that can be used to identify whether a state lawmaker has affiliations with ALEC, and how deep those affiliations run.

[198] Ibid.

[199] Center for Media and Democracy, “ALEC Politicians,” Source Watch, https://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=ALEC_Politicians.

[200] “ALEC 2019 Annual Meeting Attendee List,” Documented, https://documented.net/alec-2019-annual-meeting-attendee-list/.

Similarly, as illustrated by the successful advocacy of Color of Change and other public interest groups, advocates can have a significant impact on ALEC’s activities by undertaking sustained public pressure campaigns on corporate members to withdraw their membership.[201]

[201] Color of Change, “Targeting and Weakening ALEC,” https://colorofchange.org/campaigns/victories/targeting-and-weakening-alec/.

Fighting Laws in Committee

Each state legislature has its own legislative process. However, across legislatures, before bills are finalized for a vote, they may be referred to issue-specific committees. The legislators forming each committee scrutinize a bill’s contents before voting to approve or deny advancement of the bill. Importantly, at this stage of the legislative process, bills can be amended; if advocates are unable to stop an ALEC bill altogether, they can still focus efforts on altering its contents.

When a law is not in the interest of a state’s population and did not originate with the will of that population, the attorney general should not view it as a legitimate and enforceable statute.

The Louisiana Critical infrastructure Law discussed in Section 2 of this report was originally much more expansive and punitive than the final bill as passed. It was weakened in committee in response to advocacy by organizers and activists from 350 New Orleans and other groups that intervened to urge the elimination of a number of its provisions.

Originally, the bill contained language to allow for imprisonment for up to 12 years and a fine of $250,000 for merely conspiring to interfere with the operations or construction of a pipeline, and a minimum prison term for trespassing on a pipeline construction site.[202] The advocates successfully pressed to have these provisions removed and other language added prohibiting use of the law to criminalize or prevent a) lawful and peaceful protest on matters of public interest; and b) recreational and commercial activities in the area, including crawfishing.[203]

[202] Alleen Brown and Will Parrish, “Louisiana and Minnesota Introduce Anti-Protest Bills Amid Fights Over Bayou Bridge and Enbridge Pipeline,” The Intercept, March 31, 2018, https://theintercept.com/2018/03/31/louisiana-minnesota-anti-protest-bills-bayou-bridge-enbridge-pipelines/.

[203] Original bill: https://www.legis.la.gov/legis/ViewDocument.aspx?d=1078897; bill as passed: https://www.legis.la.gov/legis/ViewDocument.aspx?d=1097619.

A Role for Attorneys General

Civil society organizations often pressure state attorneys general to defend their state residents against discriminatory or harmful policies and laws. In recent months and years, civil society organizations have successfully rallied state attorneys general to exercise their robust legal authority to refute several policies put forth by the Trump administration that would have a harmful impact on their residents.

In the immigration context, for example, the National Immigration Law Center has issued guidance to attorneys general encouraging them to protect immigrants from the Trump administration’s targeted attacks.[204] In Colorado, the Colorado People’s Alliance has urged Attorney General Cynthia Coffman to protect the rights of recipients of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), despite threats from the federal government to repeal the program protecting undocumented students.[205] Similarly, in the case of California’s sanctuary laws, California’s attorney general has vowed to protect the state’s sanctuary laws and “defend them against the U.S. Justice Department’s lawsuits.”[206] In both instances, state attorneys general have been pressured by, but also worked with, groups like the Service Employees International Union.

[204] National Immigration Law Center, “Flexing Their Executive Muscle: How Governors and State Attorneys General Can Use Their Authority to Support and Protect Immigrants,” Last updated December 3, 2018, https://www.nilc.org/exec-authority-to-support-protect-immigrants/.

[205] Jeff Todd, “Immigration Activists Urge Support for DACA Program,” CBS Denver, July 13, 2017, https://denver.cbslocal.com/2017/07/13/immigration-daca/.

[206] Matt Zapatosky, “California Tells Local Law Enforcement to Follow Federal Law — But Not Be Immigration Enforcers,” March 28, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/california-tells-local-law-enforcement-to-follow-federal-law--but-dont-be-immigration-enforcers/2018/03/28/bee713f4-32b2-11e8-94fa-32d48460b955_story.html?utm_term=.2cb1ee754f78.

State attorneys general have also played critical roles in opposing the administration's rollback of labor protections,[207] Trump’s Muslim Ban,[208] and net neutrality repeal.[209]

[207] Attorney General Xavier Becerra, “Proposed Rescission of Tip Regulations Under the Fair Labor Standards Act,” letter to Secretary of U.S. Department of Labor Alex Acosta, February 5, 2018, https://oag.ca.gov/system/files/attachments/press_releases/Comment%20of%20State%20Attorneys%20General%20re%20Proposed%20Rescission%20of%20Tip%20Regulations%20%28003%29.pdf.

[208] Keith Ellison, “How I will continue to defend the rights of all Minnesotans as your Attorney General,” Insight News, August 9, 2018, https://www.insightnews.com/opinion/keith-ellison-how-i-will-continue-to-defend-the-rights/article_f286c10a-9bf8-11e8-87c4-afcac320541e.html.

[209] Jim Puzzanghera, “Suit by 22 state attorneys general seeks to block FCC’s net neutrality repeal,” Los Angeles Times, January 16, 2018,

When unable to prevent ALEC model legislation from becoming law, advocates can appeal to state attorneys general to not enforce ALEC-originated laws given their undemocratic origins. When a law is not in the interest of a state’s population and did not originate with the will of that population, the attorney general should not view it as a legitimate and enforceable statute.

State attorneys general may also examine whether ALEC, as a 501 (c) (3) non-profit organization, is operating in accordance with relevant state laws governing the activities of charitable organizations within their state. Again, advocates and cooperating movement lawyers can play an integral role in activating political opinion in favor of attorneys general taking such action.

Legislative instruments for transparency and accountability

Open Meetings Laws

Public access to agencies, boards, committees, and other government bodies is governed by a category of laws known as open meetings laws. These laws allow constituents to attend —and scrutinize — government meetings.[210] Most open meeting statutes prohibit members of local government bodies not just from conducting official meetings in secret, but also from conducting informal, out-of-session “meetings” outside of the public eye as well.[211]

[210] Digital Media Law Project, “Access to Government Meetings,” October 9, 2019, http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/access-government-meetings.

[211] John F. O’Connor and Michael J. Baratz, “Some Assembly Required: The Application of State Open Meetings Laws to Email Correspondence,” Steptoe, 2004, https://www.steptoe.com/images/content/9/1/v1/917/1481.pdf.

According to these laws, such informal meetings are typically defined by their purpose, to perform public business, and are presumed to be open to the public.[212] Legislative and executive bodies are required to publish an advance notice of certain proceedings, such as formal rulemaking hearings, enforcement proceedings, and other administrative matters, so that the public can plan to attend.[213] In some instances, these laws also entitle the public to copies of minutes, transcripts, or recordings.[214]

[212] Alex Aichinger, “Open Meeting Laws and Freedom of Speech,” The First Amendment Encyclopedia, 2009,

[213] Justia, “Open Record/Meeting Laws,” https://www.justia.com/administrative-law/open-record-meeting-laws/.

[214] Digital Media Law Project, “Access to Government Meetings,” October 9, 2019, http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/access-government-meetings.

Open meetings laws do have several critical exemptions that shield government bodies from transparency requirements. Meetings are allowed to remain closed when dealing with certain sensitive subject matters, including “pending litigation, the purchase of real estate, and official misconduct.”[215] Meetings are also allowed to remain closed to the public when dealing with private information about an individual, trade secrets, or other confidential information.

[215] Ibid.

Open meetings laws can support the work of advocates when there is suspicion that ALEC is meeting with a quorum of lawmakers from a state public body out of the public view. While open meetings laws vary from state to state, generally any meeting of a quorum of members of a state public entity is subject to disclosure requirements. For more specific information on the rules and regulations governing each state, see the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press’s “Open Government Guide.”[216]

[216] Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, “Open Government Guide,” https://www.rcfp.org/open-government-guide/.

Lobbying Registries

ALEC is classified as a 501(c)(3) public charity with the IRS and therefore is subject to strong restrictions on the amount of lobbying it is permitted to engage in. However, the organization appears to exist for the sole purpose of facilitating private corporate lobbying of state legislators.[217] To that end, in April 2012, Common Cause filed a complaint against ALEC charging it with misusing charity laws, massively underreporting lobbying activities, and obtaining improper tax breaks for corporate funders at the expense of taxpayers.[218]

[217] Mary Graffam, “ALEC Exposed Shines a New Light on Shadowy Organization,” American Association for Justice, July 19, 2011,

[218] Common Cause, ALEC Whistleblower Complaint, webpage, October 1, 2016, https://www.commoncause.org/resource/alec-whistleblower-complaint/.

Lobbying registration is regulated both federally and locally.[219] Lobbying registries vary greatly between states as each state defines a lobby or a lobbyist very differently.[220] In 2015, the Sunlight Foundation published a lobbying disclosure scoreboard ranking of all 50 states.[221] For example, ALEC is registered in Virginia[222] and is subject to relevant provisions of the Code of Virginia, however, the state’s disclosure requirements on political activity are relatively lax.[223]

[219] Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives, “Lobbying Disclosure Act Guidance,” Section 4 — Lobbying Registration, https://lobbyingdisclosure.house.gov/amended_lda_guide.html#section4:

[220] National Conference of State Legislators, “How States Define Lobbying and Lobbyists,” September 30, 2019, http://www.ncsl.org/research/ethics/50-state-chart-lobby-definitions.aspx.

[221] “Disclosure Legislation/ Practices : [State Lobbying] Final Grades,” Google Document, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WGGCw4eMDEdPvGGRDO7Cef_11iVRnM-XBXWRGluHsAE/pubhtml.

[222] Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Offices of Charitable and Regulatory Programs, “American Legislative Exchange Council,” Charitable Organization Database, http://cos.va-vdacs.com/cgi-bin/char_search.cgi?act=2&sysorgno=14569&orgname=American%20Legislative%20Exchange%20Council.

[223] For example, a “charitable purpose” in Virginia’s code is defined, in part, as “influencing legislation or influencing the actions of any public official” (§ 57-48), and the lobbying reporting requirements are minimal (§ 2.2-422). See: Virginia’s Legislative Information System, Code of Virginia, Chapter 5. Solicitation of Contributions, § 57-48. Definitions, https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacodefull/title57/chapter5/.

Public Records Requests

All states have public records laws that allow members of the public to obtain public records from state and local government bodies. Broadly, there are many barriers to obtaining access to government records or to certain areas of government. ALEC has taken advantage of these barriers, such as records exemptions, to infiltrate local government bodies across the country without public scrutiny.

In 2013, the Center for Media and Democracy sued Wisconsin state Senator Leah Vukmir over her failure to disclose ALEC-related materials under Wisconsin’s records law.[224] Through the litigation, it was made clear that ALEC attempts to seal its documents by arguing that they are “internal ALEC documents,” which “ALEC believed is not subject to disclosure under any state Freedom of Information or Public Records Act.”[225] Vukmir and Wisconsin Attorney General J.B. Van Hollen’s Department of Justice took the unprecedented position of arguing that Vukmir is immune from suit during her two-year legislative term. After a year of litigation, Vukmir settled with the Center for Media and Democracy and released the documents at issue.[226]

[224] Center for Media and Democracy v. Leah Vukmir, State of Wisconsin Circuit Court, Dane County, Code. No. 30952, https://www.prwatch.org/files/CMD_Vukmir_Complaint_June6.pdf.

[225] Patrick Marley, “Negotiations may end open records lawsuit against Leah Vukmir,” Milwaukee-Wisconsin Journal Sentinel, December 4, 2013, http://archive.jsonline.com/news/statepolitics/negotiations-may-end-open-records-lawsuit-against-leah-vukmir-b99155979z1-234398861.html.

[226] Ibid.

Filing public records requests, backed up by public interest litigation, has been successful in revealing ALEC’s inner workings, members, and schedules. In 2019, Documented obtained a list of members on the ALEC Commerce, Insurance and Economic Development Task Force through an Ohio public records request.[227] Similarly, in anticipation of the Republican Attorneys General Association (RAGA)’s “Oil and Gas Summit” in Houston, Texas, Documented obtained a copy of a heavily redacted draft agenda through a public records request to the office of the North Dakota Attorney General.[228]

[227] Jamie Corey, “New ALEC Membership List Names More Legislators Tied to the Group,” Documented, June 6, 2019, https://documented.net/2019/06/06/new-alec-membership-list-names-more-legislators-tied-to-the-group/.

[228] Jamie Corey, “Republican Attorneys General Group Hosting ‘Oil and Gas Summit,”” Documented, April 8, 2019, https://documented.net/2019/04/08/republican-attorneys-general-group-hosting-oil-and-gas-summit/.

For more specific information on which state open records laws cover legislators, refer to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press’s “Open Government Guide.”[229] In states where public records laws do cover legislators, advocates can use these laws to seek communications between ALEC and state lawmakers.

[229] Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, https://www.rcfp.org/open-government-sections/2-legislative-bodies/.

Disclosure of Legislators’ Expenditures and Tax Documents

Financial disclosure laws provide constituents with the tools to track conflicts of interest between a candidate or officeholder and their respective personal financial interests, or those of their donors, and the politician’s policy positions or actions in office.[230] These laws are meant to protect transparency and engender trust in politicians and in their policies.

[230] Elaine S. Povich, “State Financial Disclosure Antiquated, Inaccessible,” The PEW Charitable Trusts, October 27, 2016, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/10/27/state-financial-disclosure-antiquated-inaccessible.

In about two-thirds of states, financial disclosure forms for candidates and officeholders are available online. In the other third of states, records are accessible by filing an in-person request. In some states, officials processing record requests are mandated to verify the names and addresses of all those making a request, and mandate that requests be handwritten.[231] Disclosure laws can help advocates seek information about expenditures lawmakers make in relation to ALEC meetings.

[231] Ibid.

‘Revolving Door’ Bans

"Revolving door" bans forbid departing public officials from lobbying for a period of time after leaving public office. The laws are designed to prevent state officials acting in a way favorable to a lobbyist in return for private employment after leaving public service. The length of such bans varies depending on the state, and there are various nuances in some states’ laws. There are also restrictions at the federal level.[232]

[232] Federally, “executive order ethics pledges are one of several tools, along with laws and administrative guidance, available to influence the interactions and relationships between the public and the executive branch.” In 2008, President Barack Obama vowed to keep out lobbyists and shut the revolving door between government agencies and lobbying organizations. On his first full day as president, Obama signed an executive order to bar executive appointees from working for lobbyists that lobbied that appointee’s department for two years after leaving the government. The ban also prohibited lobbyists from working for the government department they lobbied for two years after leaving their employer. After his election, President Trump vowed to strengthen Obama’s Revolving Door Ban executive order by issuing Executive Order (E.O.) 13770 with a five-year lobbying ban. However, the Trump administration has issued so many exemptions that the operation of the law is effectively weaker. See: https://www.politico.com/story/2017/01/trump-lobbying-ban-weakens-obama-ethics-rules-234318.

Revolving door bans provide some support to advocates in monitoring whether state lawmakers are operating ethically or are making decisions that favor ALEC members in return for future employment in the private sector. Review the different state laws on revolving door bans at the National Conference of State Legislatures website.[233]

[233] Revolving Door Prohibitions webpage, National Conference of State Legislatures, August 13, 2019, http://www.ncsl.org/research/ethics/50-state-table-revolving-door-prohibitions.aspx.

‘Conflict of Interest’ Laws

Conflict of interest laws are designed to ensure lawmakers make decisions in the public interest rather than for their own personal financial gain. States have widely varying ethics requirements for lawmakers, but generally all have public entities mandated to investigate allegations of conflict of interest violations. These conflict of interest laws provide an avenue for investigating lawmakers when advocates suspect unethical conduct by an elected legislator. Review the related section of the National Conference of State Legislatures website for more information.[234]

[234] Conflict of Interest Definitions webpage, National Conference of State Legislatures, http://www.ncsl.org/research/ethics/50-state-table-conflict-of-interest-definitions.aspx.

Continuing the Fight at the International Level

UN Treaty on Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises

Since the late 1990s, public health and corporate accountability advocates from more than 100 countries have pushed member states of the United Nations to establish a robust international framework to regulate the tobacco industry. This effort has largely been led by two civil society networks: the Framework Convention Alliance (FCA) and the Network for Accountability of Tobacco Transnationals (NATT).[235] The NATT in particular, coordinated by U.S.-based Corporate Accountability International with over 100 members in more than 50 countries, was pivotal in ensuring that countries adopted a provision in the UN Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) limiting the role of the tobacco industry in formulating national health policies. Civil society groups successfully argued, on the strength of evidence exposed by litigation in the U.S. and elsewhere, that tobacco companies have a clear conflict of interest when formulating health and other policies, and have regularly sought to derail regulation of tobacco products.

[235] Kelle Louaillier, “How the Network for Accountability of Tobacco Transnationals fostered the Global Tobacco Treaty,” American Public Health Association138th Annual Meeting and Exposition, 2010,

Photo: Victor BarroTreaty Alliance members at UN negotiations, 2017. Photo: Victor Barro

NATT and FCA’s success in limiting the tobacco industry’s capture of health policy formulation has inspired activists and organizers to campaign for a similar UN human rights treaty to regulate corporate abuses of human rights generally. The Treaty Alliance, a loose campaign endorsed by more than a thousand organizations in over 100 countries, has successfully encouraged states to include a “corporate capture” provision into the text of an international treaty. In its most recent draft, UN treaty draft Article 5.5 reads: “In setting and implementing their public policies...State Parties shall act to protect these policies from commercial and other vested interests of persons conducting business activities….”[236]

[236] “Legally Binding Instrument to Regulate, in International Human Rights Law, the Activities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises,” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights,

States drafting this treaty have drawn from the language of the FCTC, which reflects the call that some UN member states, the FCTC Secretariat, and civil society organizations have made in the annual negotiations that take place at the UN.[237] In repeatedly calling over several years for this provision to be included in the future UN treaty, the Center for Constitutional Rights has several times made explicit mention of ALEC’s legacy of corporate capture, and particularly pointed to the effects of its influence on people of color.[238]

[237] Texts of interventions states and others have made to the five years of negotiations are accessible at the homepage of the UN Intergovernmental Working Group on Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Respect to Human Rights at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/hrc/wgtranscorp/pages/igwgontnc.aspx.

[238] Oral Statement of the Center for Constitutional Rights and Adalah Justice Project, fourth session of the open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights, United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/WGTransCorp/Session4/Pages/Session4.aspx.